In 2019, Kubota hosted “The Future of Agriculture: An Industry-Academia Dialogue,” a conversation between two leaders of smart agriculture in Japan: Hokkaido University Professor Noboru Noguchi and Kubota Senior Technical Advisor Satoshi Iida (Iida’s title and affiliation are those held at the time of the interview; retired at the end of December 2025.).

In the six years since that conversation, the world has undergone a pandemic, and social implementation of AI has accelerated. Agriculture has been no exception to these dramatic changes. What do these two leaders of smart agriculture in Japan think of the current state of farming and its future? They have joined again to resume their conversation, which we will present in two installments.

The first half will delve into the evolution of smart agriculture over the past six years in Japan and the challenges being faced today; and the second will explore future concepts for 2035 and Kubota’s vision for “planetary-conscious agriculture.”

Six Years of Advancement in Human-Robot Cooperation and Automation of Three Key Machines

The circumstances surrounding agriculture have changed dramatically in the six years since your 2019 conversation. To begin, Professor Noguchi, could you tell us about the research you have been involved with at Hokkaido University over these six years?

Prof. Noguchi: Agricultural technology has made very rapid progress, and the focus of our research has shifted greatly. When we last talked, we were involved in building a Level 3*1 prototype for robotic agriculture working automatically under remote monitoring. However, farming tasks are performed under a variety of environmental circumstances, so robotic machinery does not always work perfectly.

- *1. The common term for the automation level for ensuring safety of agricultural machinery as proposed by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Prof. Noguchi: So we shifted our focus toward a system in which humans and robots could work in cooperation. Instead of tasking the robots with all of the work, it will divide tasks to utilize the strengths of both sides. We are promoting a collaborative model that seeks efficiency by letting humans and robots work together and handle the work that each can do well, all while allowing humans to experience the joys of farming.

To make this possible, it is essential that robots have “thinking capability.” Our objective is to train the AI in robotic agricultural machinery with the knowledge of farm work and turn it into an intelligent partner that farmers can rely upon with a sense of assurance. We believe this will lead to development of truly smart robots that can help with work requiring advanced skills, such as harvesting vegetables and pruning fruit trees.

In these six years, what kind of product and technology development has Kubota been involved in?

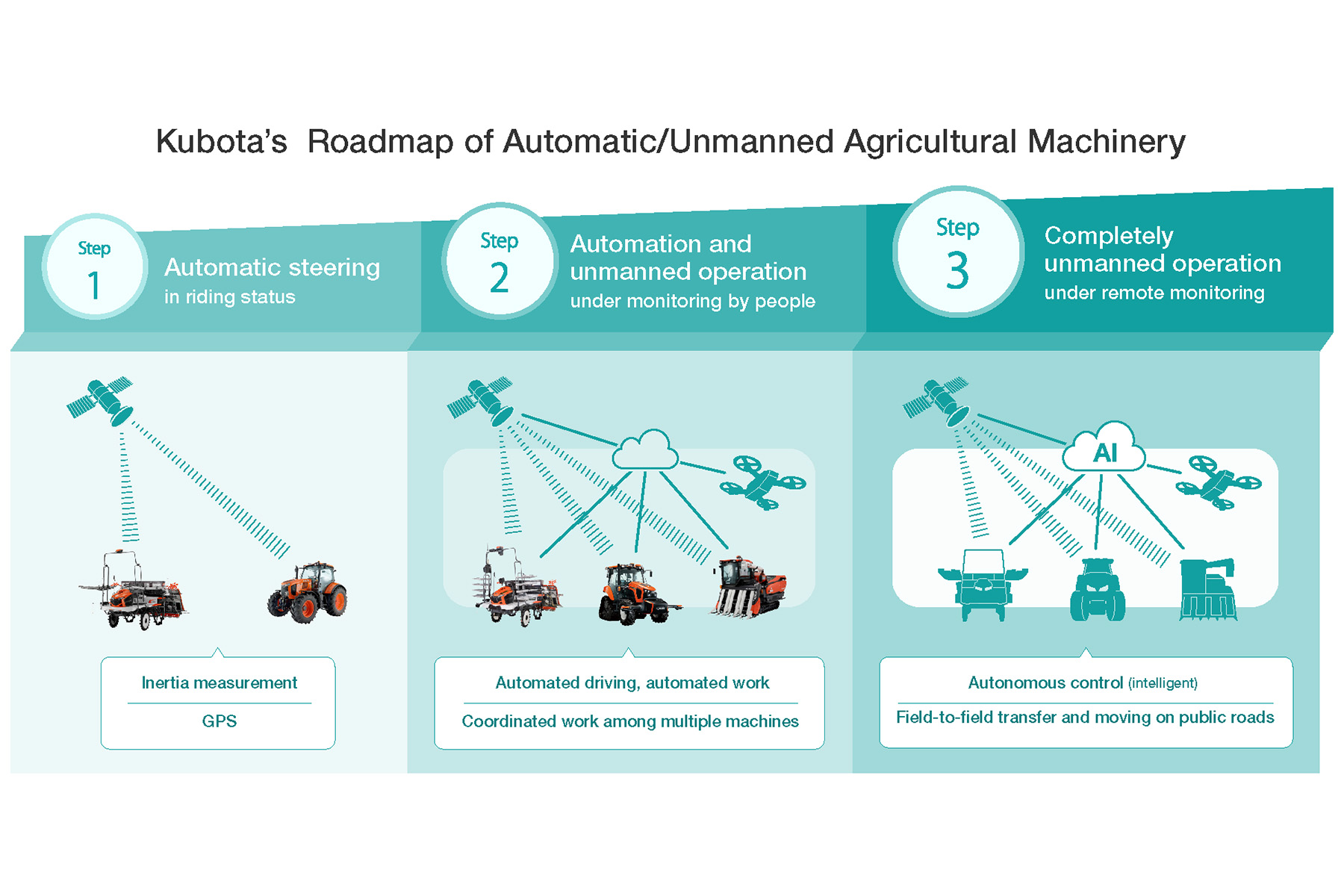

Iida: There has been major progress in two areas. The first is the achievement of Step 2, the automation and unmanned operation of agricultural machinery, or its robotization. The second is that we are just about to achieve completely unmanned operation in fields under remote monitoring, which is Step 3.

Iida: Over the past six years, we have enhanced our offerings in Step 1 agricultural machinery, which uses automated steering with a person onboard, across rice transplanters, tractors, and combine harvesters. This has significantly contributed to our business. For instance, by the end of 2024, we had sold a total of 15,000 rice transplanters equipped with straight-line assist functions.

We are now leading the world in introducing Step 2 agricultural machinery to the market, achieving unmanned operation with all three major machines. Our straight-line assist functions and Agri Robo robotic agricultural machinery are also built on the results of our joint research with Prof. Noguchi.

Open Data Innovations in Agriculture Accelerate Improvements Across Food Production Systems

Iida: Other developments in terms of data-driven agriculture are the completion of Phase 2 in Kubota’s precision farming system (Farm Management Information System, FMIS) that visualizes farm management and the conversion to an open platform. We launched a Japan-model precision farming system in the form of Phase 1 of our FMIS in 2014. With Phase 2 starting from 2019, we developed technologies such as visualization of harvests (yield/taste) for rice and dry-field farming, visualization of growth using drones and satellites, integration with water management systems, and growth stage prediction based on weather forecasts, and introduced these to the market. From here on, we will also apply these technologies to dry-field and vegetable farming as we push forward with Phase 3, with which we aim for a solutions-model farming concierge feature along with further advancements in our precision farming system.

The turning point for our FMIS was the Smart Agriculture Demonstration Project that was rolled out across Japan in 2019. Kubota took part in numerous demonstration areas, which led to the creation of an open platform that could link the external systems that farmers wanted to use with the FMIS. Now we have started providing support for obtaining J-Credit*2 and Visualization Labels*3, diagnosing weeds and pest with AI, and responding to farming-related inquiries.

- *2. A system that certifies greenhouse gas emissions reductions and absorption amounts through implementation of energy-saving and energy-reusing equipment and through forest management as tradable credits. It is administered jointly by three agencies: the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, the Ministry of the Environment, and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

- *3. A label that uses a number of stars to indicate farmers’ efforts to reduce greenhouse gases and preserve biodiversity.

Prof. Noguchi: I believe the conversion to an open platform for data is extremely important. Even a company such as Kubota would have difficulty collecting all of the data by itself, so this sort of collaboration will certainly help to improve the overall food production system.

From Eco-consciousness to AI: “Waves” in the Agriculture Industry from Societal and Technological Changes

In the last six years, we have seen societal changes, such as the implementation of the MIDORI Strategy for Sustainable Food Systems (Green Food System Strategy)*4 and the United Nations Food Systems Summit, along with technological advances with AI at the forefront. What impact have these had on agriculture itself and on the research the two of you are involved in?

Prof. Noguchi: As eco-consciousness and sustainability have become worldwide concerns, new goals have been set for agriculture. Smart agriculture technologies such as ICT and robotics will be essential for addressing environmental issues without losing productivity.

Progress in smart agriculture is being supported by technologies such as AI, satellite positioning, and 5G communications. With the utilization of these technologies developed in other fields toward various aspects of agriculture, including productivity improvements, environmental conservation, and digitizing of skilled techniques, there is a global movement brewing that is working to make agriculture more eco-conscious. Is it possible that these could serve as core technologies for realizing the recycling-based model of eco-conscious agriculture that Kubota has been advocating?

- *4. A strategy for 2050 by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in Japan that aims to achieve both improved productivity and sustainability in the food, agriculture, forestry, and fisheries industries through innovation. It sets 14 KPIs for achieving a balance between reduced environmental impact and improved productivity.

Iida: Yes, Kubota has taken advantage of the MIDORI Strategy for Sustainable Food Systems to boost its research for sustainable agricultural systems that are environmentally sustainable. There is little doubt that the new technologies you just mentioned have become the driving force behind our advancements in smart agriculture.

Among these, of course AI is causing the biggest impact. The robotics safety recognition technologies I have been studying with Prof. Noguchi could not have been possible without AI. Plus, for our unmanned Agri Robo combine, human image recognition using AI cameras is the key to realizing autonomous operation. And in greenhouse horticulture, our automatic watering control system that uses AI to detect wilting in crop leaves are among the systems already in practical use.

Prof. Noguchi: In terms of new eco-conscious agriculture approaches, Kubota and Hokkaido University are working together on research into K-IPM (Integrated Pest Management). This research seeks to find and utilize alternatives to chemical insecticides that effectively control pests while minimizing their impact on the environment.

Iida: Industry–academia collaborations like K-IPM are vital. Over the past six years, we have actively pursued partnerships with outside organizations, including collaborations with startups. Looking ahead, I believe cooperation among three fields – in-house development at machinery manufacturers, university research, and the agile development of startups – will become even more important.

The Three Challenges of Smart Agriculture as Seen by Top Players

As it continues its evolution, what new issues with smart agriculture do you see emerging?

Prof. Noguchi: One issue is that we still are not delivering technology that satisfies farmers across all crop types. Japan’s smart agriculture technology, particularly in Asian monsoon regions, has been implemented socially at a world-class level. Yet while technologies have advanced for rice farming and large-scale dry farming, they have not yet reached fruit trees and vegetables with many varieties, or hilly and mountainous regions where implementation is a challenge. Is the number of farmers making use of data actually increasing?

Iida: Yes, the number is steadily increasing. However, I get the sense that there are still very few farmers who are really making effective use of data. Farmers who are busy with day-to-day fieldwork are not always able to learn to use data on their own. The key is to help them overcome these barriers, and consulting and other follow-up support is important to help them experience the benefits of data-driven agriculture.

Prof. Noguchi: Changing people’s thinking toward using data is especially difficult in areas with aging populations. That is why it is crucial to ensure that the next generation fully understands the importance of utilizing data. Programs like Kubota’s Agri-Kids Summer Camp and summits for children, which are focused on 10 to 20 years into the future, are extremely important. I believe we are now in a transitional period, and younger generations will consider the use of smart agricultural technology as the norm.

The Role of Smart Agriculture in a Changing World

With the many challenges that agriculture faces today, do you see smart agriculture playing a significant role?

Prof. Noguchi: Yes. The biggest change I have seen in agriculture over the past six years is the decline in the agricultural workforce, which has been faster than expected. I expected some decline, but the speed has been surprising. Farmers leaving the profession is a particularly serious issue in hilly and mountainous areas*5. At the same time, I also get the sense that more and more farmers have a strong desire to preserve local agriculture and are adopting smart agriculture as they expand their operations. These two trends are happening in parallel at the moment.

- *5. Hilly and mountainous areas with many slopes and their surrounding regions. These areas account for about 40% of Japan’s total cultivated land area.

What is more, agriculture has come to be viewed now more than ever as a “business.” To ensure its viability in this regard, securing young talent is essential. We also need to promote work-style reforms in agriculture and provide more appealing working conditions. I think we will need to make this happen by providing smart-agriculture solutions to people who approach farming as a business.

Another challenge that we must deal with is climate change, especially heat damage and drought. While progress is being made in plant genetic improvements and other areas, enhancing farmers’ “adaptability” to climate change using tools such as growth forecasting, remote sensing technologies, and automated water-management systems is also a key role of smart agriculture.

Iida: In fact, there are some farmers who implemented straight-line assist machinery, Agri Robo, and KSAS and were able to double or triple the size of their operations while keeping the same number of workers. And in the Noto Peninsula, which suffered damage from the earthquake, there are agricultural companies that are rapidly expanding by making use of smart-agriculture technologies, even though they are in hilly or mountainous areas.

Prof. Noguchi: Have you sensed any major changes as you have visited farms that introduced smart agriculture?

Iida: Along with what I mentioned earlier, there has also been the emergence of farming in which women can truly thrive. Even those with little experience in manual labor can now make full use of devices such as rice transplanters with straight-line assist, auto-steering tractors, FMIS, and drones. This is clearly a transformation brought about by smart agriculture, and I believe it will be extremely valuable in light of the severe labor shortage.

Data utilization is also effective for passing down know-how. In recent years, more young managers have entered the agricultural industry from other sectors. By storing and analyzing their daily work in an FMIS, they can transfer data and expand their businesses. The example I mentioned earlier of a company tripling its scale while keeping the same number of employees as when it was founded is not unusual, and it is happening in various locations.

Japan’s smart agriculture has made remarkable progress over the past six years, but urgent issues such as labor shortages and climate change persist. Having examined both of these challenges, the two panelists will shift their discussion to the future of smart agriculture. In the second part of this series, they will discuss what smart agriculture must become in order to help the industry overcome its obstacles, and they will share their hopes for the young scientists and engineers who will lead the way.